RESCUE

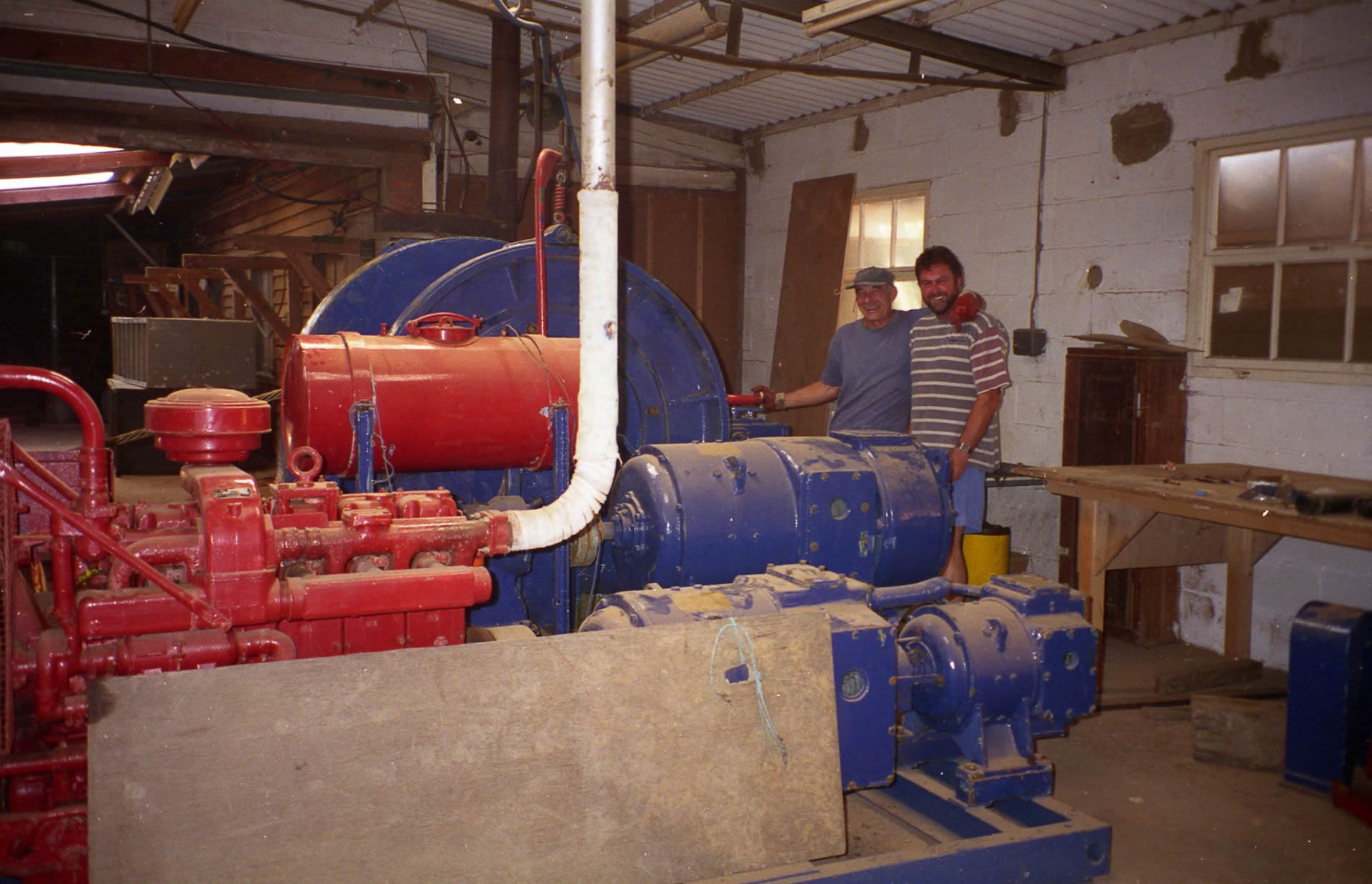

The summer saw us preparing for serious work at Whisstocks. Many measurements to be taken. The big doorway opened to a couple of inches narrower than the boat....worrying. We bought a big bandsaw, an older Wadkin planer, water tanks and a great amount of 3-phase electric wiring and sockets. Also installed fire fighting equipment and huge water tank. Benches were acquired and a shipping container for secure storage. There was a vast cradle previously designed to move even heavier ships up the slipway. This worked in tandem with a monster diesel electric winch brought from the old Cromer lifeboat station. The winch was a joy! Thunderous Dorman engine filling its shed with choking smoke through which the tall control console flashed its green and orange dials. Pure Doctor Who.

The ancient slipway had to be excavated from years of silt using fire hoses with water pumped from a distance. The cleaning could only be done at low tide. The cradle had to be eased and pushed down to the bottom on rusted wheels and rails.

The first of many days at Whisstocks. Quite a lot of interested visitors arrived, while we toiled with Tirfor winches, heavy duty skates and cables to drag the boat and cradle sideways across the yard until she was lined up with the entrance to the shed.

RESTORATION

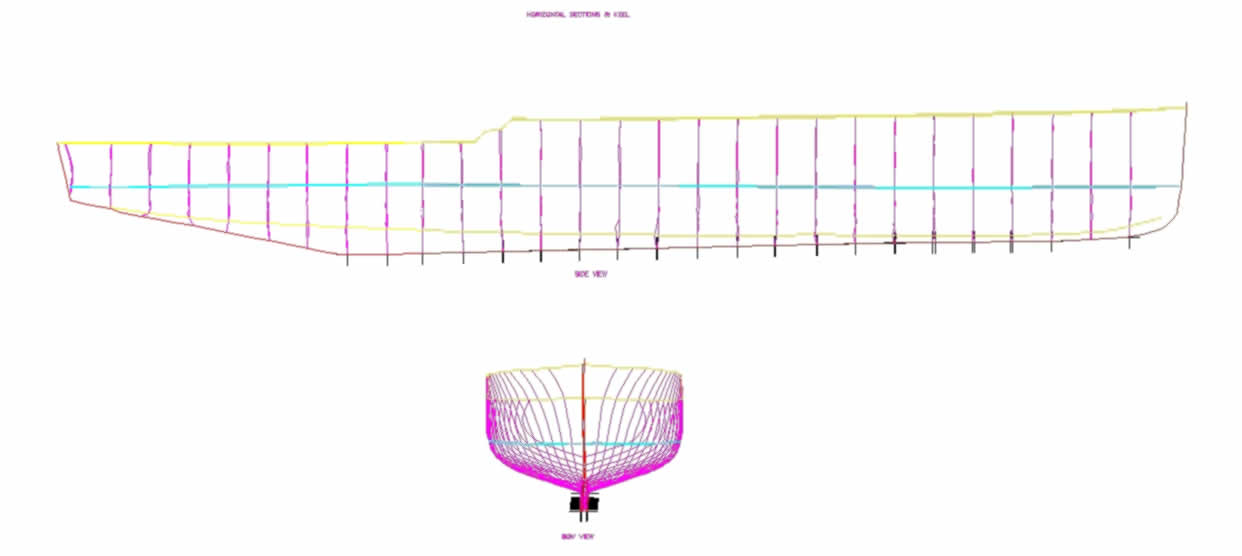

he very first job was taking the lines from her hull. A firm, just building up laser surveys for landscape architects, were asked to try the new technique on a boat. It worked brilliantly and we had a set of digital drawings on a floppy disk! Prisms and laser beams don't make mistakes.

Drawings of Ginger-Dot had been published in 'Yachting' of 1922 and we were able to overlay the new scans and check positions of bulkheads and internal arrangements.

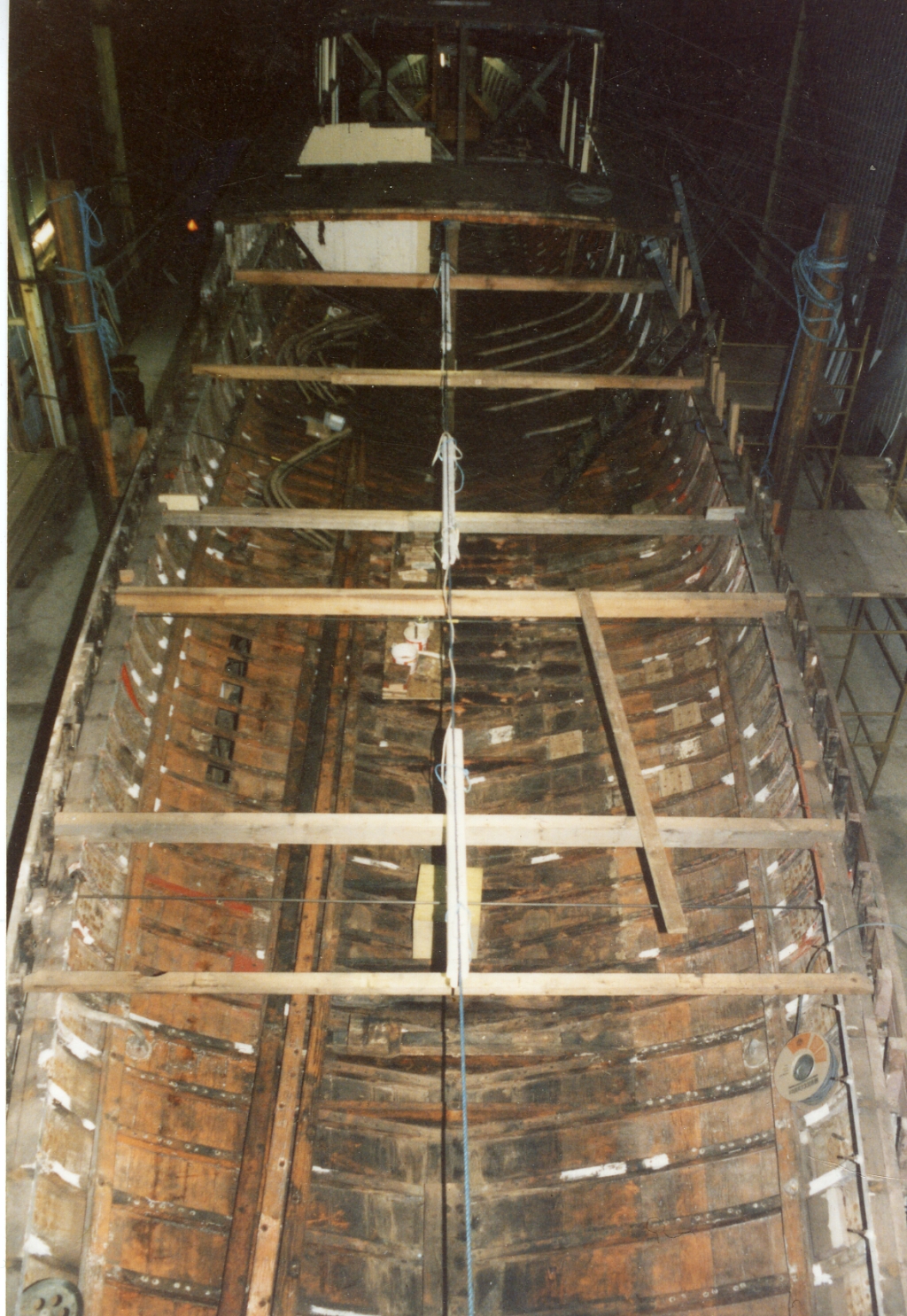

he two iron bulkheads were completely rusted away where water had trickled down from the side decks above. We had to cut them out in sections with a grinder so we could carry them out of the hull.

We decided relunctantly that we would need to steam in new oak frames along the whole length of the hull. We would need 174 lengths of new green oak prime timber sawn 2"x2", a very big steamer and at least 2000 new copper fastenings. From a purely financial view this was the moment we should have brought in a chainsaw and sold our boat for firewood... But we ploughed on.

Also at this point the main boatbuilder, Peter Benstead, had to return to a regular contract in Spain. A wise move. Winter blizzards covered the inside of the shed, the workbenches and the boat with snow. Two of the team stayed with us, Rick Davis and Jonathan Hogben, and we took on Paul Batey and David Rose, graduates from the International Boatbuilding College. Before further efforts we set about our first job all together, hastily building a large timber two storey tea room with washbasin, kettle, armchairs and an electric log effect fire! An office above with phone and electric typewriter. All very modern!

ork was heavy and sometimes dispiriting. More and more parts of the hull used as patterns only. Heavy floor sections were removed in order to drill out the 18" rusting dump pins. We made big core drills and once extracted filled the holes with cross grained oak bungs ready to re-drill. Angus turned up new bronze replacement dumps with ridges to hold in place. New keel bolts were made of Aluminium Bronze with forged heads and threads cut by Angus. Thankfully the keel seemed solid everywhere. Massive new American oak floors were bolted in and pinned to the keel.

hree consecutive pairs of engines sat in this blackened greasy space, sandwiched between rivetted iron bulkheads.We have new engines to fit - a handed pair of 1956 Gardner 8L3's. Ex 'Atlantide'. More about them later..

It was time to rebuild the engine room floor and beds. We made a full size ply dummy sump and engine mounts. The beds themselves are 4" wide 13' long tapered oak baulks and then 'flitched' with ¼"steel plate, through bolted. In addition to wood there are welded steel transverse bracing pieces alongside the heavy oak floors. At both ends these long beds are rivetted by brackets to the bulkheads using Avdel rivets. Each pair of beds support 3½ tons of engine.

e found a small firm of boilermakers still able to tackle hot rivetting and they made exact replicas of the old bulkheads. Angus acted as rivet catcher and we borrowed another industrial unit for the noisy work. Dangerously wide overhang of the bulkheads on the lorry delivery to the boatyard.

eanwhile Kim Tester ( Metalfix) was welding up twelve big stainless tanks of various shapes. All this required us to roll the boat cradle out onto the yard with winches, skates and cables again and hire a crane to lower the metalwork into place. An exciting and risky day. Boat rolled into shed again by evening. Probably a few tons heavier.

elow the waterline the planks are 2" 'pitch' yellow pine varying 10"-8" wide. These were mostly in excellent condition except where cut for the Asdic sounders. Near the bows there were some repairs and short planks so we decided to fit replacement long planks again to join to the stem.

The local reclamation yard had some very long Victorian warehouse beams 12"x 12". We somehow managed to move them by road to Frank Rout and his Guilliet horizontal rack saw in Norfolk. After hours of preliminary denailing the massive saw sliced the dirty outer wood off the beams. To our relief (the beams were expensive) wonderful, sticky, aromatic bright yellow sawdust indicated pine as good as new.

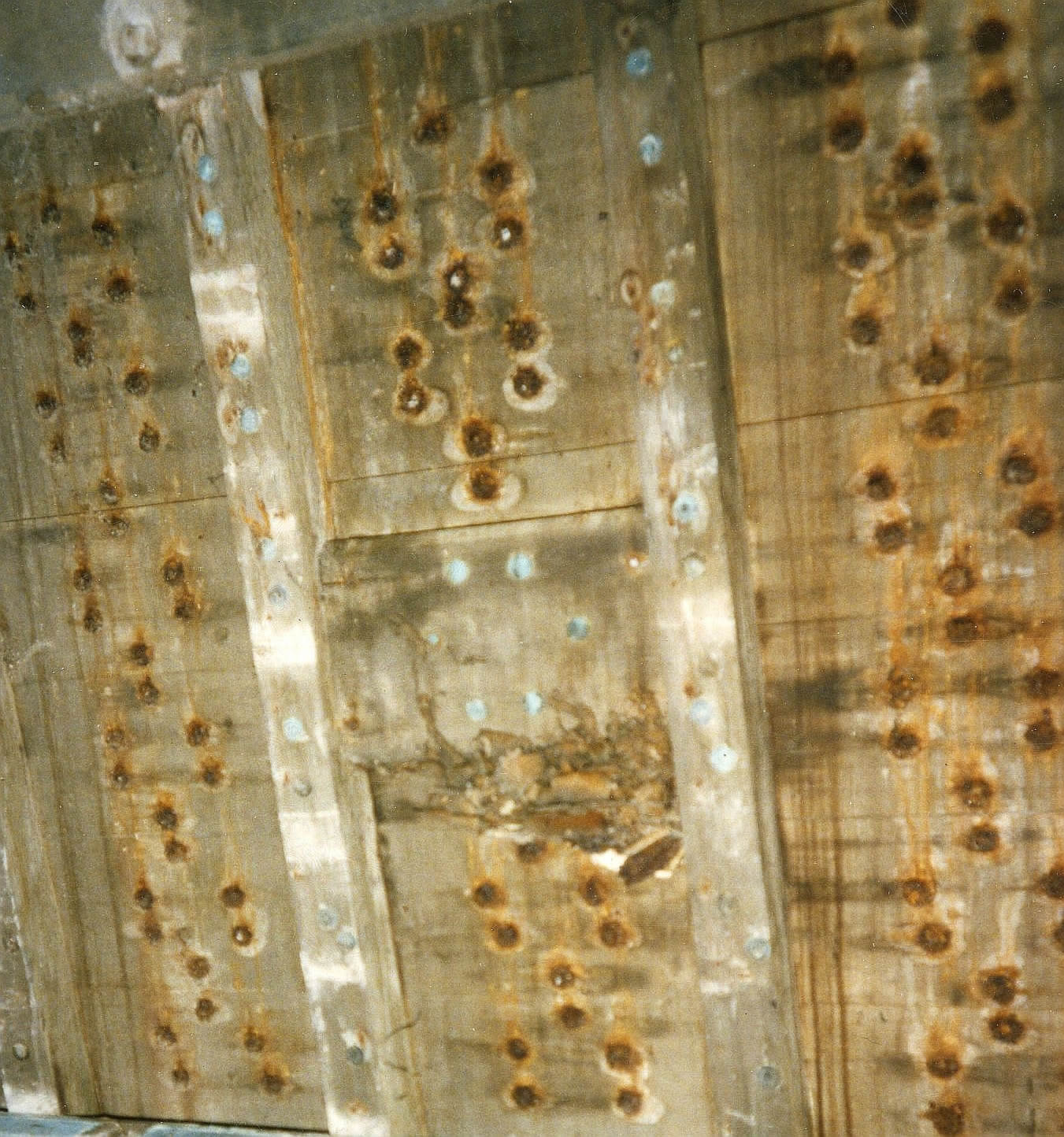

bove the waterline the 1" planks are a double layer, horizontally half lapped. They were effectively turned into one piece of timber the length of the hull by being joined by thousands of steel screws from the inside. When new the effect would be to stiffen the hull considerably. Unfortunately they were all rusty and loose and were in the way of replanking the upper hull where it had sustained the D-day damage. So many planks were dented and scraped that we ended up fully replacing these outer planks with commercial yellow pine from James Latham.. The connecting screws were replaced by bespoke oak dowels glued into re-drilled positions.

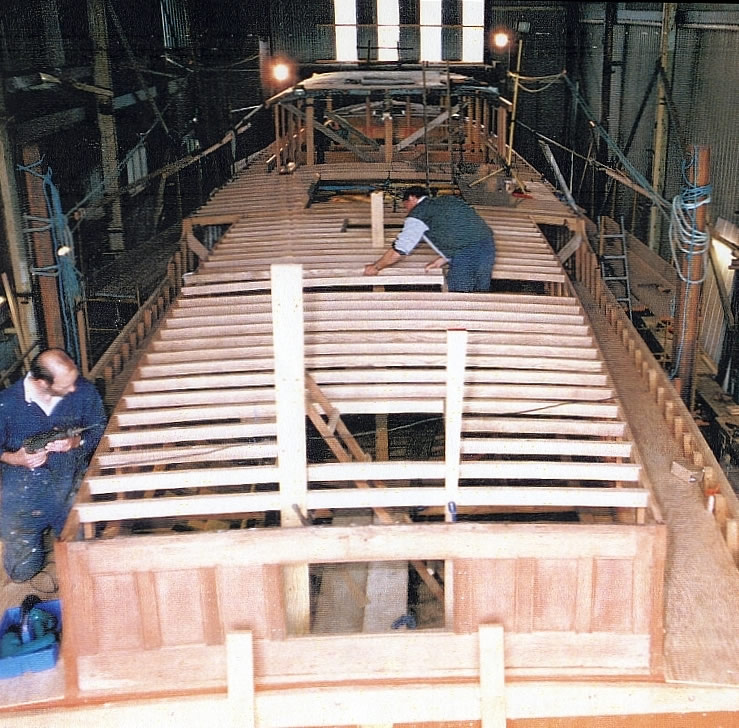

ig packs of best White Oak (American) came from Lathams. Deck beams fitted throughout the hull. The transom was removed and completely rebuilt and planked with best Teak - from Lathams of course. Couldn't buy it now at any price. That was 1997.

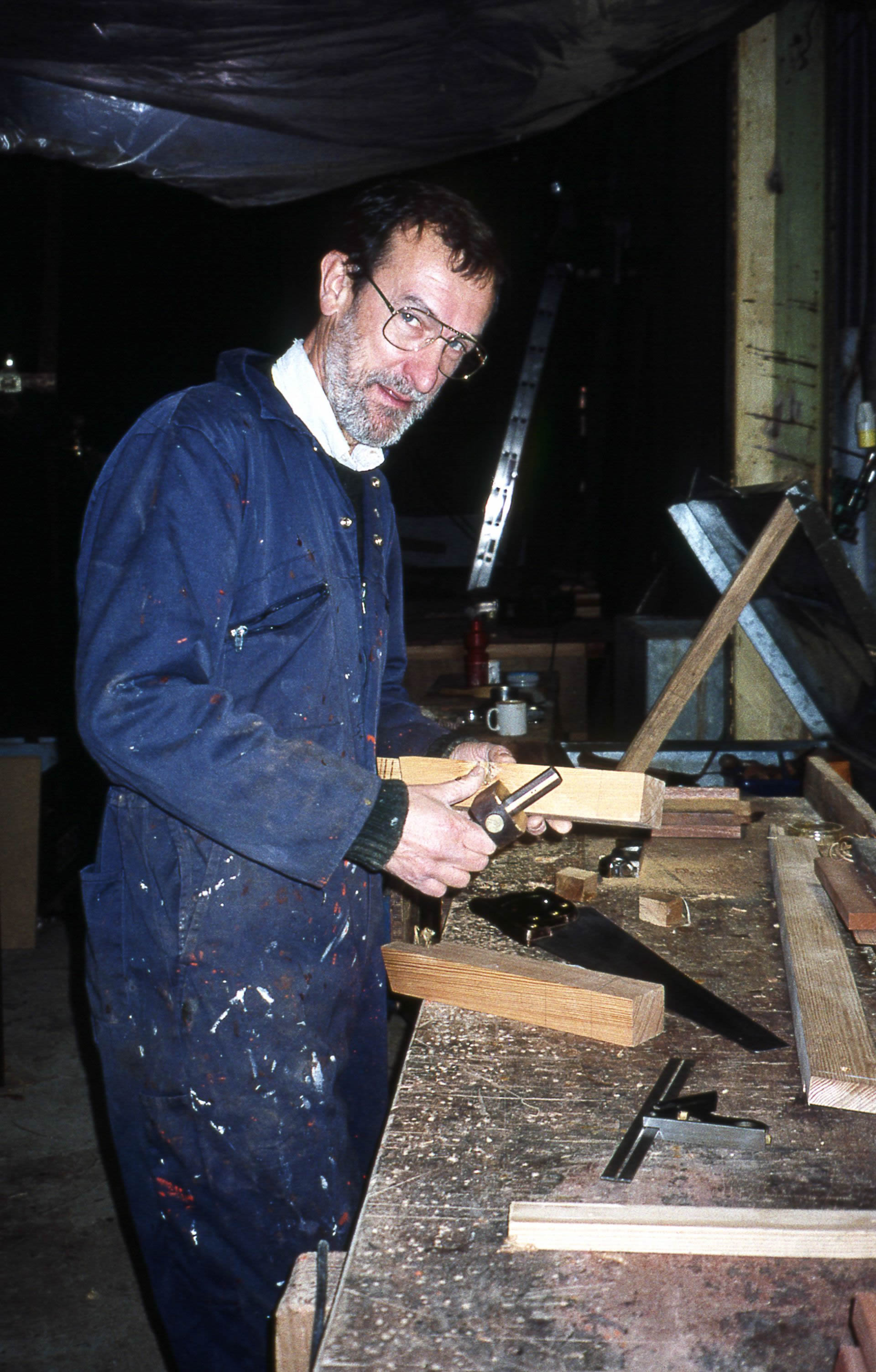

ike Greenway took the whole saloon structure down carefully and copied every part in new Brazilian Mahogany. Remaining stocks could still be garnered from various timber merchants, in particular Cushions in Norwich. The new arched ceiling beams were cunningly made by David from Oak in vertical laminations and then skinned with thick Mahogany veneer. Very strong.

round this time Paul left to go solo and enjoy more daylight and Graham returned to Ireland. Once more we looked for replacements at the College and took on Jonathan Carr and Neville Pearce. It fell to them to recreate the wheelhouse from scaled old photos. Also the engine room deck house and funnel.

he next big challenge was the decks - a full replacement. The original Port Orford Cedar is now a protected timber, expensive and almost unobtainable. It was a pale rather featureless timber from Oregon with a wonderful smell. The next best option was Douglas Fir. But in every imported pack only a few lengths were really tight grain or old growth. We searched through many packs in several timber yards. It was months before we collected enough for all the deck planks. They were machined down on our trusty Wadkin from 2"x2"to original dimensions with a very shallow half depth chamfer on one edge for the seam as original. They did a brilliant job, mostly kneeling.

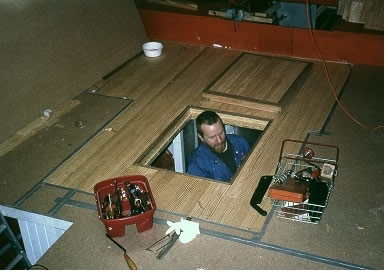

new man joined the team, an ex R.N. submariner, Karl Lemar. He had many years experience of living and working in confined spaces and an impressive history of being stuck under the north pole for several days on the first expedition.... It was our unintentional cruelty that he had the work in the tight corners. As is the case with submarine crew members he was notably good natured and tolerant. Karl and Mike had the job of building in the many tanks and a lot of old fashioned plumbing. There are, as original, large bore iron pipes right around the hull heating it, via several valves, from the engine cooling circuits.

arl went on to build rooms in the storage area under the saloon and then to lay the saloon floor. A lot of machining of cedar and fir tongue and groove boards. Later he completely lined out the forward crew quarters with cedar boarding as original and built bunks and cupboards.

ike embarked on a year of making panelled partitions from mahogany and cedar. We had plenty of original sections to copy. The sleeping and washrooms were all, as original, in painted cedar. Corridors, the 'vestibule', doors and the saloon all in varnished mahogany. His supplies came again from Lathams and Cushions. Every section was first fitted as a full size ply template.

fter much heated debate the management prevailed with the plan to use Coal Tar Pitch for all the caulking of seams. The more normal choices between Jeffreys Marine Glue or black Sikaflex were rejected as being unsuitable. Jeffreys because it ages to bituminous soot and Sikaflex because it was not suitable to be used in very narrow seams and also has a limited life span.

So called ' Tar Pitch' will last more or less forever, has a waxy surface, can be poured as a hot liquid and if cold becomes extremely hard. All temperatures between allow it flow and re-settle indefinitely. It is wonderful stuff!

However handling the material was a steep learning curve. In its hot liquid state it will stick fiercely, particularly to metal tools. The solvent is Cellulose Thinners or Xylene. Petroleum based thinners like White Spirit don't touch Tar but can be used as a lubricant for scrapers. At less than very hot it becomes waxy and can be handled, rolled and stood upon without stickiness.

We bought supplies of new plastic cartridges and heated the 25 ltr drums until pitch flowed into an iron tank with a gas burner under and a plug tap outlet. When hot the tap allowed the filling of the cartridges. When ready to use later the cold cartridges, with plunger inside, were cut and a nozzle screwed in place. Then they can be re-melted in a bath of boiling water, the tip cut and tar injected into the seam while runny, with a cartridge gun. In cold weather the seam needs pre-warming with a heat gun to allow complete fill before setting. All very simple really!

ormal stringy caulking cotton seemed inadequate for the joints of our 2" deep seams. Over here in the UK we couldn't buy the much bulkier American cotton which comes in big skeins. It has to be split into the required thickness and then wound into a ball. We soon built a setup to do this and imported the cotton from USA.

The seams were first painted with red lead in oil and then, over the well packed cotton, the filling was a stiff compound of red lead, oil and cement powder. The hull below the waterline then got two coats of warm Tar.

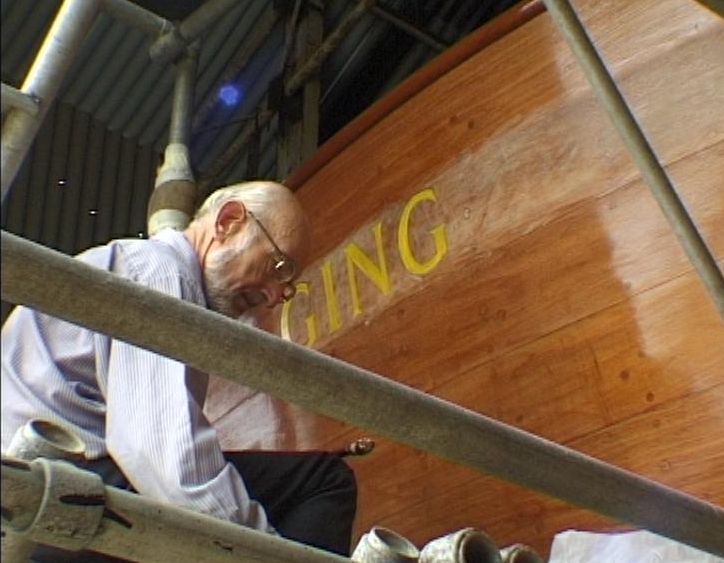

wo pieces of work were beyond our skills. The repair and re-carving of the Luders signature scrollwork on the bows and the gilded lettering on her transom. We were honoured to employ a brilliant woodcarver, Tom Staddon, who lived in the area and had just finished working on the repair of the Music Room at Chatsworth - Grinling Gibbons I think. He returned the scratched and battered scrolls to perfection. He also carved and gilded her nameboards - one can be seen on the home page of this website.

e were under notice to end our occupation of the boatshed. The initial lease for two years had been extended twice more and the owner was negotiating the sale of the whole yard and buildings. A high tide date was set in September 2002 and preparations started in the summer to prepare the crumbling slipway for use. River mud had completely submerged the whole structure again in the seven years since last use.

This time we met the need for a sluicing water supply by hiring a big fuel tanker and using our Coventry Climax pump to fill with water from the river at high tide for use at low tide for water jetting. In a week the slip was clear to its derelict lower reach.

he seized plain bearing wheels of the cradle had to be jacked up at each corner ( only 20 tons...) and made free again. The whole kit of cables, Tirfor winches, big shackles, skates and heavy steel sheets had to be hired in again. All in all the September date came up too soon and the next high tide was early October.

hen the day dawned skies were dark with rain. We had hauled the boat to the yard area at the head of the slip the previous day. Some advised to send her down with a 'whoosh' into the river. We felt, in respect of the slipway and snaking rails, it would be safer to let her down slowly at low water and wait for her to be lifted off the cradle. First we dismantled the river wall....

A

sodden crowd stood watching as the winch payed out its cable in stages and another smaller electric winch wound a cable pulling downwards via a pulley at the bottom of the slip. With groans and little lurches the vast load descended as planned. The time came around 1 pm for the predicted flood tide which would gently lift her off her chocks and the cradle but fate played a cruel trick. The full river height was well below the forecast. The tow boat struggled against the odds to tug her off but she still held firmly at the sitting bows while her stern, already afloat was tugged this way and that. This was enough to dislodge the unweighted lower part of the cradle right off the rails and nearly off the edge of the slip. She was stuck and her chocks floating away.

s the feeble tide retreated the rain grew heavier. The crowd shuffled off and only the kindest and most determined helpers stood around discussing what to do next. The chocks were broken but wedged back where possible. The worst fear, that as the tide left she might fall over, luckily was averted.

Tam Grundy suggested he enlist the help of a friend with a seriously big tug from Felixstowe docks. The next high tide was due to arrive around 1 a.m and the tide might be higher. We grabbed whatever food and waited, feeling exhausted and very worried. If we failed our seven years of work could be ruined.

As the inhabitants of Woodbridge slumbered, at the appointed time, the sight of something lit like a huge Christmas tree appeared round a bend in the river. Our tug rumbled gloriously towards us, its spotlights shining on the stricken vessel. Mel Skeet and Tam were out in boats to attach lines and Mike was already aboard 'Ginger-Dot' with his foghorn!

The tug tugged. At first nothing and only much churning of the wake and then, very suddenly, our old lady leapt off the cradle and shot right across the river narrowly missing the tug and Tam's boat... Mike blew the horn. The grand visitor from Felixstowe just slipped away again and Mel was left to take over the dropped bow line and coax our surprised ship into line, pointing upstream. Torches and spotlights were forbidden as Mel regained his night vision after all the lighting dramas. The huge white boat slid off into the black night. Heard the foghorn again in the distance.

e all dashed off to Melton Boatyard in our cars and arrived in time to help secure her alongside a pontoon. Now the onboard generator had everything aglow and Mike remarked on all the little tiny jets of water spouting up in the bilges!

n twenty four hours the leaks were gone. Mike bravely spent the remains of the night on watch while we all slid off to our cots. The next morning, early, we had to set things to rights at Whisstocks. With the aid of strategic jacks and cables we managed to move the crashed cradle back on its rails, dismantle the flood barrier again and winch the cradle back into place in the yard.

That began a month of stripping out all our machines, containers, fixtures and fittings and moving it all back home - another story.